Like all people, scientists too are very much different from one another. For some, life is a more serious journey, and for others, it is a bit more playful. Some prefer to retreat into solitude because it is the only way they can work in peace and listen to the muses of creativity whispering subtle sounds in their ear, while others prefer to spend their down time in the company of their students.

There, they discuss matters of great seriousness or, on the other hand, the very everyday ones. Some are true loners, others are eccentric like those we see in movies, such as the notorious Californian wave surfer who in 1985 discovered the then most convenient way to quickly duplicate pieces of the DNA helix in the laboratory, without which we probably wouldn’t have been able to even imagine an effective solution to the global crisis of the COVID-19 pandemic. The stories of these are, of course, what historians of science are particularly enthusiastic about.

Of all the biographies of Nobel laureates I have read, the one that has stuck with me the most is a photo of Kip Thorne at the 2017 Nobel Prize ceremony, laughing in tears, crouched over a book of Nobel laureates with a photo of Albert Einstein and his signature. An image that will go down in history as a unique symbol of a moment in time when past scientific discoveries meet the modern, and when the triumph of honouring a brilliant scientist like Thorne is completely dissolved by the respect for the work of a man who had such a profound impact on succeeding generations. A man whom Thorne respected and adored from a young age, and whose theoretical predictions were confirmed nearly 100 years later when gravitational waves were observed with the LIGO detector, earning Thorne his Nobel Prize.

Einstein’s hypotheses, his work and the immense power of his influence astound us year after year – last year, of course, being no exception … let me highlight three of these that concern time.

Last year, when scientists at the Swedish University of Uppsala observed the states and interference patterns of Rydberg atoms, they discovered a new method of measuring time, called “quantum timestamping”. The ripples of an atom packet in the experiment can act as a different ‘fingerprint’ of time that can be measured. This method will be particularly effective where traditional timekeeping is not yet possible, for example, observing the states of extremely fast electrons carried out in femtoseconds. It will be particularly useful in the development of quantum computers. Scientists at the University of Toronto have observed what they call “negative time”. When they studied photons travelling through a cloud of atoms in the laboratory and interacting with the atoms in the cloud, at the end of the experiment some photons ‘appeared’ to have exited the cloud before even entering it. Later, to avoid too much confusion, scientist Sabine Hossenfelder clarified that the experiment does not in fact have a direct link to time itself, but simply demonstrates how photons (in this case localised packets of energy, which are waves) travel through a medium, quickly downplaying the excitement about time travelling “in the opposite direction”.

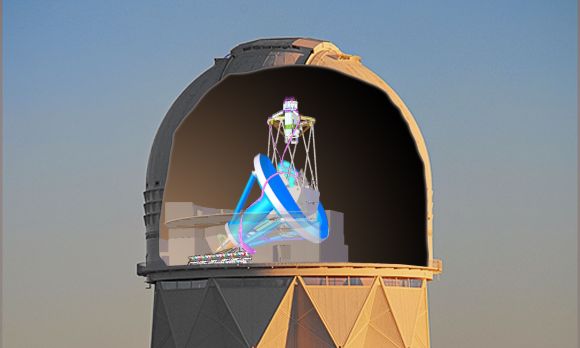

Arguably one of the most important discoveries touching on the problem of time last year has been the analysis of data from a spectroscopic instrument called The Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI), which has confirmed Einstein’s theory of general relativity to the greatest extent yet. At the Kitt Peak Observatory in Arizona, scientists have found that the very way galaxies evolve and the way billions of galaxies merge is perfectly consistent with what Albert Einstein had predicted many years earlier. This data has given scientists a very detailed map of the Universe, allowing them to study the largest number of galaxy distributions, galaxy formation processes and galaxy dispersions over time to date. It is this data that not only supports Einstein’s Theory of Gravity, but also offers us new opportunities to study dark energy, the currently enigmatic force that drives the accelerating expansion of the Universe in time.

The question of what time is has always intrigued thinkers, philosophers, scientists and artists around the world. Doing a little research in literature not strictly scientific, one of the most influential western books dealing with the question of time was H.G. Wells’ The Time Machine, published in 1895. It fascinated readers with the idea of a mechanical device that enabled time travel. The detailed descriptions of the time machine and its construction were the basis for countless stories that followed the popular novel, which was not only a groundbreaking science fiction read for its time, but also offered a critique of the social and economic conditions of the time. It offered the reader a scientific framework for the exploration of the past and the future, until then completely unknown, and thus allowed them to imagine the possibilities of such a journey and its consequences.

By contrast, astonishingly advanced contemlations of time can be found much earlier in eastern literature. In the Mahapharata, the central work of Hinduism, which scholars call the world’s longest epic or the longest “poem” in history, the story of time travel can be found, going back thousands of years before in 1907 Albert Einstein introduced the world to the phenomenon in which the observer’s own time in an observing system differs from that in a different observing system. It is called time dilation, which in simple terms means that time passes at different speeds in different parts of our universe. According to an ancient story described in the Mahapharata, king Kakudmi and his daughter Revati visit the god Brahma, seeking his advice. When they return to Earth, they discover that 116 million years have passed, described in the book as 27 periods known as Chatur Yuga. This can also be interpreted to mean that time passes at different rates on different levels of existence. Therefore, a second where Brahma exists corresponds to a time of many years on Earth. This story is one of the earliest records of time travel in literature and is one of the great examples of the advanced understanding of time and space by the ancient peoples of India. And yet this is just one of the stories in the ancient Indian epic where the characters travel to distant places and experience great differences in the passage of time.

Currently, a time machine cannot yet be store-bought, but it is something that can be considered, which some physicists do in all seriousness, or, in the words of New Scientist journalist Leah Crane, the ideas that are currently popular among physicists about how to travel through time could, after careful consideration, be divided into three principal ideas. The first would be to use the classic ‘warp drive’. According to this idea, we could sit in some sort of a bubble that warps the universe and time before and after the bubble. As one moves with the bubble, the fabric of the universe, called ‘spacetime’, literally moves with them. Since this way one is not really moving, this would allow one to bypass the speed limit in the universe, which is of course the speed of light, and travel back in time. The only problem is that this process requires a huge amount of negative energy, which is something we can already generate now, but in extremely small quantities.

Another idea is to create a massive laser light ring, and as this huge ring rotates, it literally pulls time behind it. This produces a time loop that allows time travel. The problem with this is that we would need a ring the size of a galaxy for it, which is not (yet) feasible. As she says, the most ‘feasible’ method with the knowledge we have today is one that takes into account quantum mechanics. This allows us to send very, very small particles back in time. This means that with this method, time travel is not yet possible for humans, but we could send a message back in time, or change something extremely small in the past, which would subsequently, through the ‘snowball effect’, result in a visible change today. So it seems that we won’t be travelling back and forth into the past and the future just yet. But who knows what the future may bring …

On the end, I should mention a thing or two about the end of time itself, or as one of the most famous science communicators and theoretical physicists at the moment, the Englishman Brian Cox, put it– Let us say that you somehow manage to get over the edge of the black hole that we call the horizon and, because there is no other way, you move inexorably towards the very centre. Towards that centre, which as yet no physicist actually knows what it is, but which we still have a name for, and we simply call it singularity. So, taken Einstein’s theory, which has so far worked brilliantly for such problems, this is a point in the Universe that is almost infinitely small and dense, and where everything in the Universe is ‘mixed up’. And so this is a point where even time no longer exists, and which, according to Einstein’s calculations, can be downright called the ‘end of time’.

Andraž Ivšek

Ljubljana, 13. 01. 2025

The article “The time in Enstein’s theory and traces of that time in eastern and western literature” was presented on the The second Slovenian-Indian Day of Science and Innovation on 16 January 2025 in The Crystal Palace BTC, Ljubljana.